In California and many other places, climate change and land-use patterns intensify disaster dynamics where one thing leads to the next. In this text we will look deeper into how wildfires affects the drivers that increase the flood potential.

Normally, soil and vegetation do a good job of absorbing rainwater. After a wildfire, scarred soil and burned vegetation block water absorption. And when the next heavy rain comes, the water masses bounce off the soil with increased flood risk.

It never rains but it pours

The sunny state of California is no stranger to floods. It has 38 major rivers and river floods are by far the most common event type. All 58 counties of the state have experienced at least one significant flooding in the past 25 years, which resulted in loss of life and billions of dollars in damages. On top of this, flash floods from heavy downpour represent an increasing problem for Californian communities.

Just during the last year, repeated flood events have impacted the state. The Federal Emergency Management Agency declared flood-related disasters in January 2023 and in March-July 2023. Media reported on a series of local, regional, and state-wide floodings over the year (as illustrated by CNN news feed).

Burned landscapes

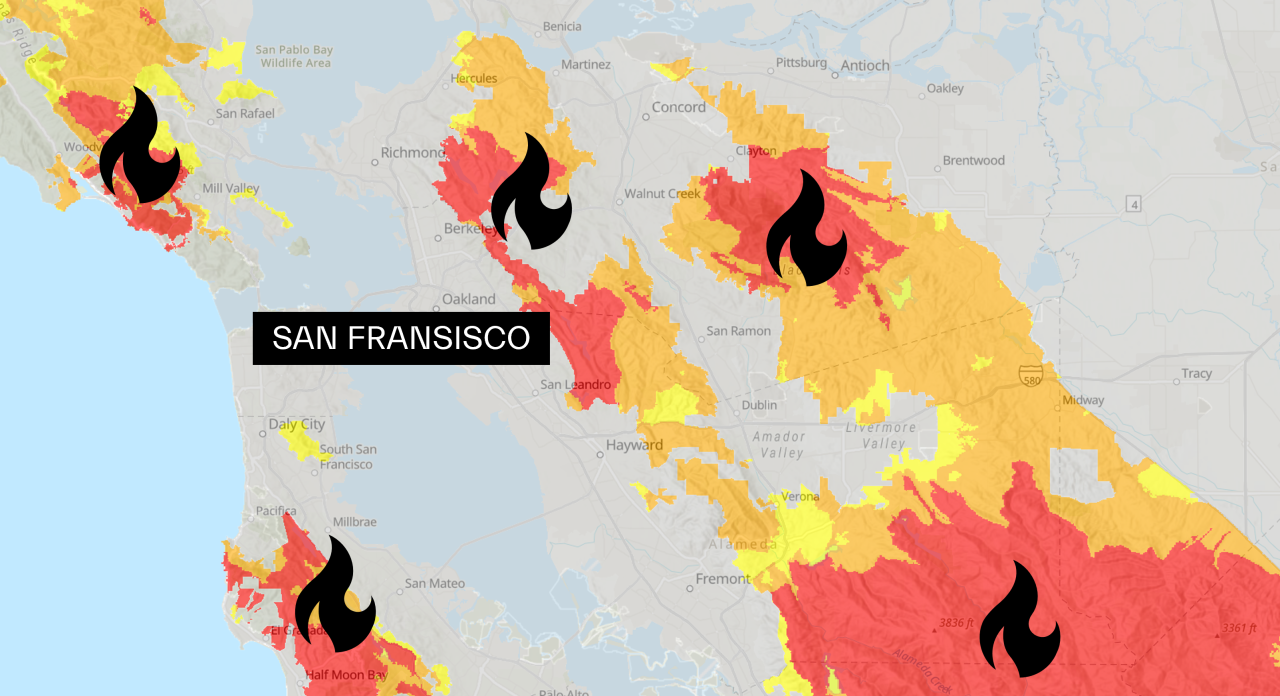

Though somewhat counterintuitive, California struggles with both floods and fires. The environmental pollution, property losses and casualties caused by wildfires in the state are getting worse by the year. Add to this that the extent and severity of wildfire is expected to increase in the future, mainly because of fuel accumulation and climate change. Already now, the wildfire season has lengthened and the peak months have been advanced from August to July.

Looking at historic trends, both frequency and total burned area of all wildfires have increased significantly since the turn of the century.

Wildfires have burned through large areas in recent years, leaving burn scars behind as lasting impact on the landscape – and adding to the risk of flood.

Fire-flood dynamics

A wildfire consumes vegetation and leaves behind a landscape which is covered in soot, ash and charred stumps and stems. It abruptly changes the hydrologic and soil properties of watersheds decreasing infiltration capacity and changing soil surface structure. For example, an ‘ash crust’ can be formed or the underlying soil can become water repellent due to a hydrophobic layer of burned organic matter.

Intense rainfall after wildfire can result in substantial overland flow and potential for flash floods. Furthermore, the risky dynamics involves elevated chances of mudslides which may be even more impactful than extreme water flows.

In California, studies have shown that wildfires enhance flood risk in the first two years after wildfire; however, the effects diminish after another two years.

Severe dynamics

The links from one disaster to the next can quickly have severe consequences. When the Tropical Storm Hilary stroke California in August 2023, the authorities issued a flood warning specifically to those living in wildfire burn scar areas encouraging them to evacuate.

In the Arroyo Seco watershed in Southern California, detailed studies have identified how great the fire-flood dynamics can be. Following moderate to high burns, the first year since fire demonstrates that a 100-year flood can be three times larger than non-fire-affected years. When a rain heavy weather system passes, a flood peak flow three times over can make the difference between no issues at all and severe flash floods with detrimental consequences for affected communities.